The day my father died, three months ago yesterday, I was at my mother’s house helping her to move out of our family home. It was nearing the end of the two weeks I’d spent with her laughing and crying through the packing up of 40 years of tat, trinkets and family treasures.

I was alone, sitting on the verandah and lamenting that this would be the last time I could enjoy the spring lushness of the sub-tropical paradise that my mother had created in her garden, when the phone rang. It was my younger brother.

‘Pam?’ There was a pause. ‘Dad is dead.’

The words hit me in the gut and seemed to ricochet around the room in the damp, misty KwaZulu Natal air. They left me doubled over and breathless. Maybe that is what drowning feels like.

Earlier that day, you see, my 76-year-old ‘fit-as-a-fiddle’, ‘firing-on-all-cylinders’, ‘going-to-live-to-150’ father had met his end in a hot spring in a hotel three hours out of Tokyo.

Never one to toe the line or act his age – one of my friends once described him ‘as the most immature adult he’d ever met’ – my father had decided to stay on in Japan for an extra week, while his martial arts’ group, the people he’d being doing a course with, returned to South Africa. He’d also, apparently, not followed up on a fainting episode in Frankfurt airport a year earlier, which would have brought to his attention an underlying heart condition that makes exposure to high temperatures dangerous.

On a Skype call that morning, soon after hearing the news, my sister in Austria tried to comfort me: ‘Well Dad was never going to have straightforward death. He died as he lived, spontaneously.’

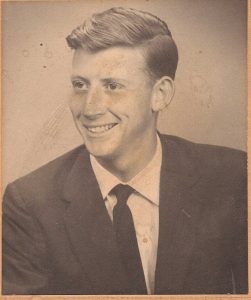

My father certainly hadn’t lived a straightforward life. He arrived in South Africa on a boat when he was 10, at 12 he lost his brother to meningitis and at around 13 his Irish Catholic mother, who in her grief had taken to the bottle, abandoned him to his doctor father who, probably in his grief, had found solace in another woman (a Belgian World War 2 spy for the French resistance who would become Dad’s stepmother and our Grand-mère). He left school at 16 and took his first job, visited his birth mother in New York at 18, where he heard her version of the truth of his parent’s marital breakdown, and married my mother less than ten years later at 26. That’s the short skeleton of the story of his early life, but it was just the beginning.

My parents married young, in 1967, a few month’s after my grandfather’s sudden heart attack, and the celebration was named wedding of the year in the local newspapers.

Wedding of the year!

When my grandfather dropped dead at just 48, this too was widely covered by local press. Leigh Cocks had been one of the few survivors of the bombing of HMS Cornwall in 1942 and after the war had started a sports club for young boys in Westville. There is even a sports field named after him, in the sprawling suburb just out side of Durban.

My maternal grandfather, Leigh Cocks

So, I think it’s probably fair to say that my father fell in love with my mother but also with her family. With the exception of my gay great uncle, who I suspect my father later resented for the influence he wielded, and the time he spent with us, by contrast to his own fractured upbringing, this ‘normal’, happy, close-knit cocoon must have been just what he was looking for.

[Ironically, by some accounts, it was my great-uncle, a psychology lecturer at Durban University, that my father took to lunch at the prestigious Natal Yacht Club to ask his advice on how to break the news to the family that he was leaving my mother for another woman.]

Perhaps my grandfather’s death was a bad omen. Eight years of marriage and three children later, in 1975, my parent’s separated. I was five.

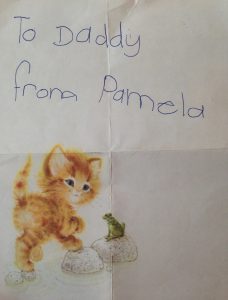

A kitten and a crying baby

My father left in January in the humid height of a Durban summer but my memory of that day is one of wintry, watery sunshine. My older brother and I helped him as he methodically loaded his belongings, including a walking stick which must have been his father’s, into the boot of the car. Before he drove off to start his new life, he knelt down and hugged us. He told me that he loved me and would see us soon.

Ching the first and me, 1975

My brother locked himself in the bathroom and cried and I went into the garden to play with my new Siamese kitten –

for a five-year-old, there is nothing quite like a cute animal to take the edge off your father leaving. Meanwhile, my mother sat in the living room holding the crying baby, my two-week old brother.

Some would say my father’s actions were unforgivable, and if you believe in karma then he certainly got his ‘comeuppence’.

Wheeler, dealer…

After marrying his second wife, the mother of my two wise and wonderful sisters, the bright lights and big bucks of Johannesburg beckoned. Here, in the early 1980s, my father made a fortune wheeling and dealing.

In one of the many letters we received after my father’s death, an old colleague wrote: ‘He was the ultimate dealmaker. Make a million today, lose it tomorrow.’ The letter goes on to refer to the pair of them flying to Namibia in ‘one of my father’s planes’.

One of his planes! Just the one? This was the first I’d heard of it and, if I’m honest, the line raised my hackles, as through those very 1980s my mother always seemed to be struggling to make ends meet. What I did know, however, is that at this time my father always drove smart cars, wore posh shoes that he’d bought in London, drank expensive whisky, smoked cigars, owned a racehorse and moved steadily from one big house in Johannesburg to another. The biggest one – a pseudo Tudor mansion with a tacky mish-mash of clashing styles including some ostentatious art-deco bathrooms, an oak-panelled study and a sweeping grand staircase – spanned three blocks, had four wings, countless bedrooms, a swimming pool and servants’ quarters. The vulgarity that came before the fall.

It was here, after the market crash of the late 1980s, and into the early 90s, that my father’s financial decline accelerated and he lost just about everything – planes, properties, his second wife and their two young girls. He did, through it all, however, manage to retain his sense of humour, dress the part and drive a fairly smart car; appearance mattered. Somewhat ironically, although you might have expected that this would put even greater strain on his personal relationships, this tumultuous period in my father’s life marked the beginning of the healing of our then somewhat broken bond.

Dad celebrating with Sally-Anne (left) and Suzanne (to his right)

If Dad thought things were bad then, they were about to get worse. In the April of 1992 his second ex-wife passed away tragically and overnight my father was thrown into full-time parenthood, becoming both ‘mum’ and dad to two young and strong-willed, yet vulnerable girls with whom he developed and unbreakable bond. He was their father, but would also become their best friend.

Still, as I now understand, it was a difficult time and it certainly stretched my father’s short wick; and at one point my own mother even offered to help raise the girls. Unsurprisingly, he refused, and instead came to rely quite heavily on the elder of my two sisters, who was a young teenager at the time.

Coming to ‘true’ parenting later in life undoubtedly helped my father to face up to his own flaws and the hurt he had caused, and after I had my own two children he would often say: ‘Darling, never ever forget that your children are sent to teach you.’

…healer?

With his wounds of childhood rejection, the pain of two divorces, financial ruin and unexpected death, my father unquestionably faced some grim and lonely times. And from the jottings in his notebooks and on scraps of paper found in the books that my sisters passed on to me after clearing his flat, it’s clear that he went through a period of intense self-reflection.

At some point, he fully abandoned the Catholic Church, which he said was ‘all about men in control’, in favour of a more esoteric, tree-hugging form of spirituality. He practised yoga, self-taught in his 20s, took up Tai Chi, and other less known forms of martial arts, and meditated daily.

He worked hard to make peace with the people he knew he’d wronged – including his children and my mother, who he phoned to apologise for the difficulties he’d caused her. And in searching for forgiveness he found what he believed were his own ‘healing powers’.

Absorbing energy!

Yes, now our wheeler, dealer father had transitioned into ‘healer’! This extraordinary self-belief, which was part of his ‘work on himself’ and involved ‘letting go of negativity’ and the ‘sins of the fathers’ became a later life mantra. If I’m honest, this sometimes grated on my nerves; my father was the embodiment of positivity to the point of being delusional.

But maybe I was wrong.

On one trip, after visiting us in London, he took a taxi to Heathrow and got into conversation with his Iraqi driver, who he handed his recently printed ‘healing services’ card! God knows how this conversation started and ended but the upshot was that this man’s wife – let’s call her Katarina – called my father in Johannesburg a few days later for ‘healing’. That same week my father rang to ask me to have a coffee with her because, he said, she ‘needed some TLC’. This, with some eye rolling, I reluctantly agreed to; from what my father told me, Katarina sounded interesting and, if nothing else I thought, it might lead to a story. At the time I was seeking out women with interesting tales to tell for interviews, and a German-Russian immigrant to the UK who was willing to call a ‘healer in Johannesburg’ fit the bill.

Even more unbelievably, during this meeting I soon discovered that Katarina’s children attended the same school as mine and we even had a mutual friend. It was this mutual friend who passed on the news of my father’s death and soon after came this message from Katarina via WhatsApp.

‘What bad news about Francis…he was in reality one of the best spiritual teachers I have ever met…he definitely played a role in helping us create a happy marriage…he was so friendly and cool, able to find a way to touch anybody’s heart within minutes of talking…he taught us hands on healing techniques that we will never forget…what a loss to so many people…’

And so, through disbelieving laughter and tears, it went on.

Contradictions and colour

That there were so many people present at my father’s memorial struck me both entirely credible and a little odd. Although my father loved to charm people – not always successfully – and actively sought out conversation with whomever he met, behind the bravado he was, I think, insecure, needy and a little bit lonely. In his thoughtful, reflective moments he would be known to say: ‘If you can count two people as true friends then you can count your blessings’.

So while there were at least 200 people at his memorial service, there could just as easily have been two. Yet present were those two ‘best friends’, who supported him through and in spite of everything, his family (including my mother), at least three of his ex-girlfriends, his loyal and beloved staff, the ‘spiritual’ camp, his accountant, builder and broker, former colleagues and business partners, and the South African Japanese and Chinese martial arts group, which he was travelling with the week before he died.

My father wasn’t a perfect husband, ex-husband, friend or father. In the three eulogies on the day of the memorial said by my older brother and his two best friends, and in conversations at his wake, my father was described in a multitude of ways.

Among the words and phrases used to describe him were: ‘love-hate’, ‘obnoxious’, ‘spiritual’, ‘a womaniser’, ‘generous to a fault’, ‘arrogant’, ‘thoughtful’, ‘inspiring’, ‘delusional’, ‘a light being’, ‘dogmatic’, ‘hard-arsed’, ‘hot-headed’, ‘away with the fairies’, ‘unforgettable’, and a ‘very fine man’. As my friend Mick, who became a close friend of my father, said when I rang him to tell him the news: ‘Your Dad definitely wasn’t everybody’s cup of tea, but he was mine.’

All humans are full of contradictions but my father, it seems, was more so than most. With watery eyes Ruben, his long-standing, faithful driver of 50+ years put it this way in his gruff 80-year-old crackle: ‘Aah, yes Mr Whitby, Mr Whitby. Do you remember Pamela: “Ruben this isn’t a hotel, this is not a bloody hotel.” Aah, yes, Mr Whitby, he could be hard but after shouting he would always say sorry.’

It’s true. My father was very quick to flare, but just as quick to apologise and also to forgive. He also knew how to laugh, both at himself and with others too.

If nothing else, my father’s esoteric memorial service and wake, and the people present, were a reflection of his multifaceted, contradictory but very full life. He was the centre of attention and a present force: he would have loved it.

Wanderlust

‘Francis was completely client focused – a lesson, which remains with me is never ever get a person’s name or title wrong. He was smart and meticulous – numbers were checked and rechecked. Then checked again,’ one former business partner wrote in a letter.

This attention to detail, sheer hard work, spades of determination, ‘positive energy’ and an ever-present entrepreneurial desire to succeed, helped my father get back up on his feet and out of debt. He began to rid himself of ‘pointless possessions’ and moved into a small lock-up-and-go ground floor flat with a patch of green. On this he would grow the organic vegetables and herbs that he thought would help cure his stomach complaints and the acute psoriasis he had developed in his later years. He was always going to cure himself, something that probably also led to his early demise.

In Ireland on a trip with Suzanne in 2011

He wanted to travel and for the first time in years in had the means to do so. He visited my sister in Colorado, and again when she returned to Austria with her husband. With them he went white-water rafting, quad-biking and skiing. Then there was the healing course in Cornwall and the journey to the pyramids of Egypt. He also visited the ancient sites of Ireland with the elder of my two younger sisters, a country that through his birth mother he felt deeply connected to. On this journey, he sadly did not feel able to reconnect with his Irish family who never really forgave him for the divorce.

Swimming in the Indian Ocean

Although he was born in Datchet, Buckinghamshire, and spent his early years there, he loved Africa and nothing would have dragged him away from the continent, which he was always incredibly bullish about. He made regular trips into the bushveld and to the mountains and coast – especially the east coast’s warm Indian Ocean, which was good for his skin and which he loved to swim in – and where we will scatter his ashes this December.

He came to visit us in London too. One year I’d promised to buy him some expensive leather slippers; the one’s he’d bought when he was flush had finally worn out. Needless to say my father was delighted when the shop assistant (a woman!) thought I was his wife (Thanks sister!). Me less so; I like to think that this is because he looked like the sort of man who might go for a much younger woman, rather me looking the same age as my father, who from about the age of 55 hadn’t seemed to age at all. That same day, showing off in a posh, overpriced shop on Jermyn Street, he decided to buy a sleeveless cashmere pullover, which at the time he couldn’t afford but said he ‘needed’ to stave off his increasingly frequent chest infections as a result of those freezing winter mornings in Joburg.

Back at my home in southwest London, later that afternoon, he came downstairs sheepishly. ‘Darling, I think you might need to take this back for me. I was being a bit lavish.’ Not only had he learnt to apologise, but also to live within his means!

One of the last photos my father took in Japan

His wanderlust culminated in his trip to Japan. In one of his last emails he wrote: ‘My trip to Japan is a booking with my martial art’s group but I am looking into the possibility of staying on a bit longer. I am also considering going on to India if that is affordable. Seeing that I will be in that part of the world why not? I have wanted to go to India since I was a child.’

It must be love

Although I’d visited South Africa last year, I hadn’t seen my father because my mother had been so unwell and she was and always has been, quite rightly, my priority – this my father really did understand and did not resent. But I did feel guilty and in an attempt to compensate I suggested that he spend Christmas or New Year with us in London. He loved and was proud of Fergus, and he wanted to spend more time with his London grandchildren. We were all looking forward to it.

But that was not to be. Sadly, or perhaps not depending on how you spin it, on October 12 2016, a hot spring in a small hotel three hours outside of Tokyo would become my father’s last stop.

Would Dad have been happy with his own death? Forever positive, I can almost hear him saying: ‘Well, what a way to go…’

Personally, I don’t believe my father was ready to die but maybe it is that I wasn’t quite ready for it and I have some regrets. Should have called more, should have said this, shouldn’t have done that …Wish I had…If only…

What I do not doubt, however, is that my father loved me, and all of five of his children. It may not always have been ‘perfect’ love but as my younger brother put it, it was unconditional.

In the box with my name on it that my sister delivered to me after clearing his flat was a file. In it, every note, letter, card, postcard and drawing I’d ever sent him (not to mention a reading about my future from a psychic he’d visited in 1978!). One note with the picture of a kitten and a frog in the left-hand corner reads simply: ‘To Daddy, From Pamela’.

Seeing this again triggered an early memory; my brother and I were in the car at the edge of a park on an outing soon after our parents separated. I handed my father the note and recall him opening it in anticipation and then asking me sadly why I had written ‘from’ and not ‘love from’. I’m not sure that at five I would have consciously withheld the word love, but it was a very early lesson in what actions hold power.

My father spent his life searching for that elusive ‘perfect’ love because in the end he realised that this was all that mattered. And despite our fragile, and sometimes complicated relationship I loved him back, as authentically as I could – and I wish he wasn’t dead.

My relationship with my father wasn’t perfect but the love sticks. What also sticks, clichéd though it may sound, is the importance of remaining positive whatever life throws at you. Maybe because he so desperately needed to forgive and be forgiven, my father was also keen on forgiveness. Guilt trips were never his style.

So, to hell with regrets. Today it’s freezing in London and the brief snow that turned to sleet has cleared, and they say temperatures are going to plummet further over the weekend.

You’ve been dead three months Dad but later this afternoon I’m thinking of heading into town to splash out on some cashmere. Because, as you would say, ‘you can’t take it with you’. And, anyway, the fashion bloggers say I’m going to need it.

Images: Some of my own but also from Dad, Richard Whitby, Suzanne Whitby, Sally Whitby and Fergus Clegg

What a wonderfully honest and loving ‘sort-of tribute’ to your father, Pamela! I greatly enjoyed reading it. Your father sounds like a great character and someone I would have really liked — mostly because, like my own father, he seems to have known how to enjoy his life. That is a very special trait.

Thanks Alex. From you, whose writing I greatly respect, this means a lot. Tough to write but healing too, but yes, my father definitely knew how to enjoy life – a special trait and a lesson for us all.

How candid and mighty pure of you Pamela.

There are lessons for us all not just in the unique prints that your father on the path that he trod but also in how we must nurturer the seeds of latent love to full bloom in order for us to fully harvest the gift of life!

Thank you

Not sure about mighty pure David!! But thank you for taking the time to write a comment – and, yes, lessons for all of us to harness the gift of life.

Pamela this is so beautifully and honestly written. Before I had read any of the other comments, I myself had thought how therapeutic it would have been for you, especially as I had been with you at the time that you heard about your dads death. I met him at Barclays Bank Maydon Wharf ,where we both worked, he being my boss, so could relate to a lot of your tribute!! We had a lot of good laughs over the years and I would have liked to have been at his memorial, but the distance didn’t allow it at the time. Glad you are moving on with life as that is what he would have wanted you to do…happy shopping xx