There are two things that South Koreans love to talk about – the country’s four distinct seasons and the food.

These were two things that I came to talk about too. The seasons: the hot thick humidity of summer and its threat of acid rain; mountain walks in autumn through trees drenched in red, ochre, gold and fading green; the arrival of the icy Siberian wind in winter, and the cycle of a three-day freeze, followed four days of relative mildness; and then the relief of warmer weather and the explosion of cherry blossom, cerise hibiscus and milk-white magnolia in spring.

And then there was the food. In the year I spent in Seoul, which began in the summer of ‘96 and drew to a close in the spring of ’97, it came to be the centre of everything. You could find delicious freshly cooked food everywhere; on every street corner, in markets, in tents and in the traditional places with their sliding doors made from hanji, a locally made rice paper. In that year, I barely cooked a single meal. Eating out was like eating in.

So important is eating to Koreans, that the standard greeting is bap mogosoyeo; literally translated this means ‘Have you eaten rice?’ So, one of the most useful first bits of advice I received was to learn to read hangul, the distinctive and elegant alphabet developed in 1442 by King Sejong the Great and which has remained the official script of North and South Korea ever since. This made it possible to read menus, as few were translated into English back then.

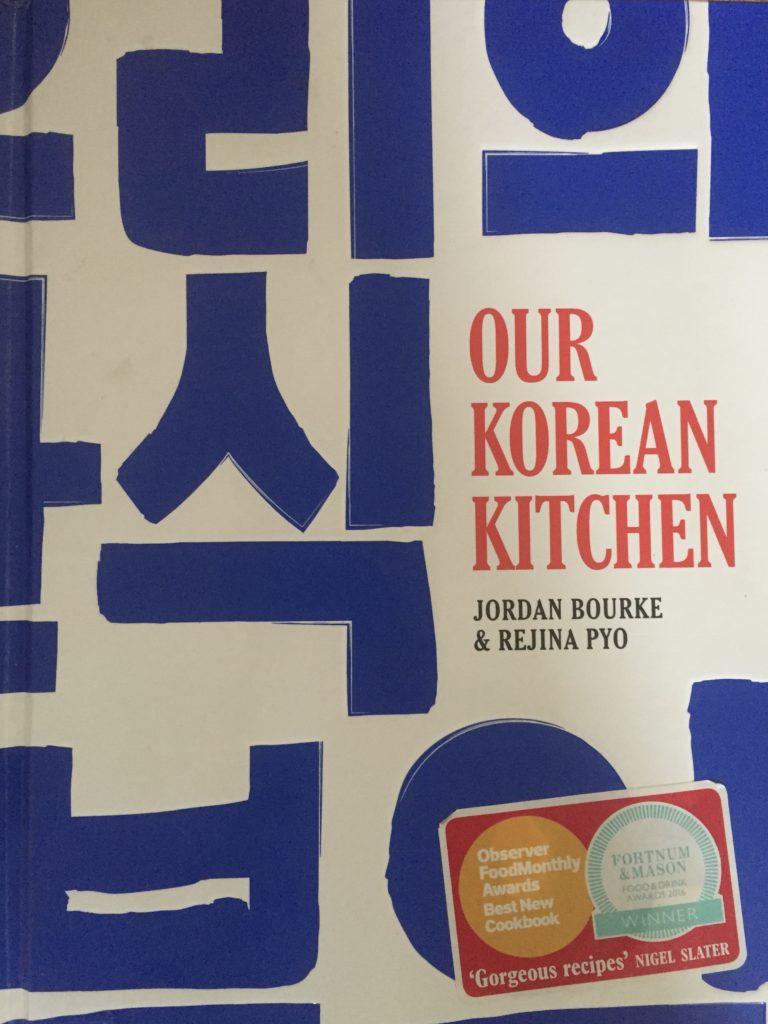

Last month, I found myself thinking about the year I spent in Seoul. There was a birthday celebration in our house and we allowed ourselves the luxury of driving to purchase some provisions from the Korean supermarket in New Malden, a suburb of southwest London. Since lockdown began, I’ve started to use exotic recipes more. I find it takes me back to places that I yearn for and probably won’t have the luxury of travelling to for some time, perhaps ever. That’s if some forecasts that post-Covid 19 long-haul journeys will become a luxury again are true. This time it was Our Korean Kitchen, last year’s birthday present, and one of the books that is helping to put the best food in the world on the map!

Steaming and sizzling

I remember the day I landed in Seoul clearly. It was early morning as the plane descended into Kimpo International airport and to the east lay the coastline of Japan. Below the high rise of Seoul, which is sandwiched between the four mountain ridges of Namsan, Bugaksan, Naksan and Inwangsan, emerged from the haze. I had just missed the monsoon season and it was the first and last day of that summer that the air was relatively clear but the heat was muggy and oppressive. It was heat like I’d never experienced, even hotter than a sweltering summer day in Durban, the sub-tropical city in South Africa where I grew up. A city I also long for.

My first meal was lunch at a typical street side establishment with two South African friends who were living and teaching in the city and had arrived a year earlier. Like many of the small establishments that you could find on every street corner, the décor was basic; it had simple tables with metal legs, plastic coated menus, bad strip lighting and delicious air-conditioning!

Their choice for lunch was samgyetang – a steaming soup of baby chicken, garlic, jujube, ginseng and rice – which seemed an odd decision. But Natasha explained that Koreans eat this dish in the height of summer, supposedly to keep energy levels up, and to regulate their body temperature with that outside. It is a dish I have come to love but I recall staring at the whole flabby bird floating in a clear yellow broth, and shivering with jet-lagged nausea.

Later that day, after an afternoon nap, we sat cross-legged on the floor in a more traditional establishment. This time it was Bulgogi, translated literally as ‘fire meat’, which is cooked on a sort of upmarket in-door barbecue, or skottel braai for the South Africans reading this. Thin strips of beef, marinated in soy, ginger, pear, sesame oil and gochuchang, the distinctive red pepper paste, are cooked in minutes over gas in the centre of the table, and then wrapped in lettuce leaves with sticky rice. As with every meal, it was also served with all manner of kimchi, including the most common version that I made last month.

Cult status

The Korean supermarket had everything that I needed. Chinese cabbage, spring onion, daikon, an enormous phallic looking radish, gochuguru, the essential red pepper powder, garlic, ginger and onion. In my store cupboard at home, I already had soya and fish sauce, table and seasalt, rice vinegar, honey and flour, and in the garden there were chives. To share in the car with the family as we hadn’t eaten lunch, I also bought some kimbab, the Korean equivalent of Japanese sushi, only better in my opinion!

At the checkout, after handing over my loyalty card and paying, I thanked the young woman. ‘Ah, how do you know kamsahabnida, ‘ she said, and although I couldn’t see her mouth beneath the mask, her eyes told me that she smiled. I explained that I’d spent a year in Seoul, and my plan was to make kimchi, the fermented cabbage staple that is served with every meal. She sounded surprised: “Ah! Have you made it before?” The truth is no, even though its health benefits are now achieving cult status and my family love it.

The reason for this exercise was that earlier that week I had been inspired by Yvonne. She had sent me a photo of some that she had made – ‘delicious and surprisingly easy to make’, she wrote in a WhatsApp message. This is not true. It requires chopping, crushing, processing, stirring, and patience, one of my old friend’s many qualities but not mine. Perhaps my experience was down to the quantity I made. As it turns out, I had under estimated the weight of the cabbage, and had bought two instead of one; one, a kilo, would have been enough for the recipe. And even though I’d bought the smallest radish, that weighed 800-grams and recipe required just over half that, so I was just short of enough ingredients to make a double portion!

Ancient wisdom

Making kimchi is a slow process and I rushed the first bit. This meant that I had a whole sink full of separated cabbage leaves, rather cutting it lengthways in half and keeping the base in tact. The cabbage leaves must first be rubbed meticulously with sea salt, paying particular attention to the thicker end of the leaves, and then soaked in dissolved table salt, turning once in four hours.

Between finishing a whitepaper about the US petrochemicals industry, and getting to grips with the chemistry of plastic making, I found myself going downstairs every 30 minutes or so to check on the chemistry of my kimchi experiment. In four hours, the salt had finally wilted the cabbage leaves into a bendy, unbreakable state and they were ready to be rinsed and rolled into the paste of onion, red gochugaru powder, gelatinous flour sauce, ginger, honey, the sauces and sixteen cloves of garlic!

Another two hours and I was done, my hands and lips spice stained and burning, and two 2.5-litres jars almost full with red silky cabbage leaves, slithers of radish, spring onion and chives. It looked delicious. Delicious! mashesoyo, mashesoyo, I thought, making a little bow like the restaurant owners in Seoul always modestly did to express gratitude for your delight in their food.

Another two days at room temperature and my kimchi was ready to try. The family liked it but personally I thought it got better and better as the days passed. When I posted the photo of my jars to Facebook, my very first Korean friend Heon Yeong posted: ‘OMG what achievements!’

It really did feel felt like an achievement but it also felt like more than that. It was comforting, comforting and grounding to have made something rooted in the ancient wisdom of the east, and knowing that this long perfected practice of preservation will endure way beyond this coronavirus crisis.

Journeys

Another two weeks and all that was left of my first batch of kimchi was enough to make a kimchi jigae, a soup of pork, spring onion, sesame oil, tofu and the famous cabbage.

Suddenly I am transported to a happy day towards the end of 1996. My friend Heon Young and I have taken the train out of the city and we are having lunch at a restaurant perched on the side of a hill. It is late autumn, and she has ordered us steaming bowls of my all time favourite soup. Outside the sky reflected in the Cheonpyong Lake is a still slate blue. Over this meal of the ‘best ever kimchi jigae‘, she translates for me an ancient Korean proverb – ‘should a white handkerchief soak the sky in autumn it would turn blue and make blue raindrops’.

That summer of 1996 had shifted into autumn and the trees on the hillside were a rich red, not a far cry from colour of the cabbage leaves that were fermenting in my kitchen on that locked down Thursday in the April of 2020.