The long rectangular boxes were the obvious place to start unpacking. They had been around forever, since the Floral Duet days. During school holidays, I would sometimes help in The Shop, as it was known. It was exciting when the wholesaler truck arrived with boxes tightly packed with florist staples – everything from long and short-stemmed roses to Alstroemeria, sprays of Chrysanthemum, Gipsophila, Gerberas, Lisianthus, and more.

I took a deep breath and cut the tape holding together the first of three battered boxes. It was crammed with floral paraphernalia – disintegrating bits of oasis, pin holders, florist wire, and countless pairs of secateurs, scissors and pliers. How many does a florist actually need?

The second box was brimming with washed out dried flowers, skeletal leaves, palm spathes, wood roses and pods of the lotus plant. Mostly dead stuff.

Before I got to the third, Richard appeared, after a smoke break, in a vision of pink tie-dye and rainbow coloured pantaloons. Gesturing at the open boxes, he said: ‘Chuck it out Pamela! Chuck it all out. She won’t be using any of that again and there isn’t space. David said we must get rid of as much as possible before Mom arrives on Monday.” My younger brother and sister-in-law had done the really hard work, packing up the room in Kwa-Zulu Natal in just a few hours.

“But it is her life’s work. It might be useful to show the social worker next week what she might like to do,” I said.

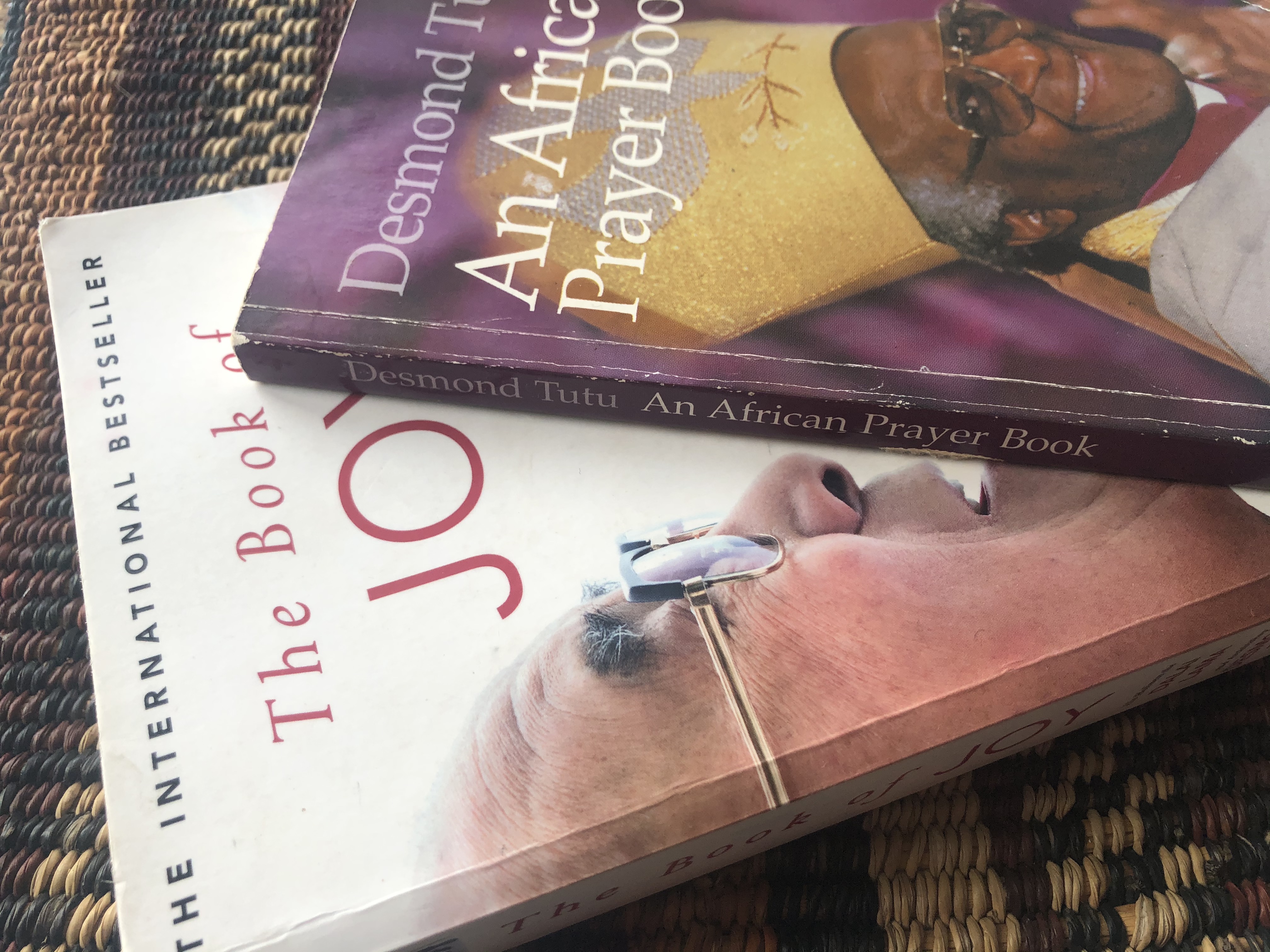

I knew my brothers were right. After her fall in September, which cut short our mother’s life and robbed her of the last fragments of mobility, she would not be using her hands again. She couldn’t feed herself, let alone stand. And there wasn’t space. But I wasn’t ready to – it is painful choosing what to throw away when somebody is no longer able to decide. And so I pushed the florist boxes aside to sort out later in the day and started on the one labelled books – among them dog-eared collections of crossword puzzles, Desmond Tutu’s African Prayer Book, Tutu and the Dalai Lama’s Book of Joy, a worn Illustrated Guide to Southern Africa, the Roberts Bird Book, one with drawings of rare South African flowers, countless others on floristry, and a children’s picture book of Psalm 23.

The following week, after our mother had arrived in Johannesburg, I asked her if I could gift the picture book to one of the family with young children. Her response was: ‘No, not yet, it’s a good one. I need it.’ I guess she was looking forward to those still waters and pastures green.

When we got to the boxes labelled breakables, we both looked at each other, and Richard said: “I need a cigarette.” I needed a large gin.

One of first of the bubble-wrapped objects was the crystal bowl, engraved with the words Best on Show, Chelsea 1995. “Now that is something to show the social worker,” my older brother said, as he disappeared with another box of stuff to take to the dump. I continued to unwrap the breakables: bud vases in trumpet-shaped solid silver, Waterford crystal and turquoise ceramic; clear glass vases in the shapes of spheres, squares, rectangles and cylinders, and a tall one in light-showering red; not to mention the pair of voluptuous naturally glazed teal Lois Mulchays, which she had bought on one of the trips to Ireland.

away – It was too big and too delicate to fit it in my suitcase.

The end of something

On my last visit, I placed a bunch of small flowers, picked from the care home’s wild and natural gardens, in my mother’s battered working hands. Watching her attempt to arrange a tiny posy, it struck me that this was as much an act of instinct as it was of determination. On the way into the building there was a large pot of mint. “Pick some of that Pamela,” she said. Her voice was almost a whisper, and she just managed to bring the sprig to her nose.

Mom enjoyed that final small arrangement in one of her crystal bud vases, one of the many that has returned to London with me in my suitcase. They have joined those I brought back, after we packed up our last family home at Bartle Road, five years ago. There is the shapely elegant stone-tone pottery cylinder that I had bought for her as a gift after my year in South Korea. It was never a ‘working’ vase; instead it took pride of place on the pelmet at Bartle Road. It is embossed with cream chrysanthemums which, I had explained, were a symbol of loyalty and fidelity. Perhaps she didn’t want that to break with the one who had moved away.

There is also the sturdy oval teal vase that held the last remaining bouquet, one of many sent by friends in the UK. It was the one I binned on Friday because they were, as Mom would say, ‘on their way out’ and the slime-stink stems and water reminded me of the The Shop. The dusky pink roses, tulips, and miniature daisies looked beautiful but I could not help thinking that the blue gum filler was, in Mom’s words, one of the ‘aliens’. In South Africa, Australia’s blue gum trees, or more correctly Eucalyptus, are responsible for 16% of the 1,444 million cubic metres of water resources lost to invasive plants each year.

When you receive flowers it is uplifting and when you throw them away, it is the end of something. It is just over four weeks since our mother died, so it may be that I will have to brace the cold and go out to pick some hellebores, narcissus, perhaps some fruits of ivy, and a sprig of flowering rosemary – it is still too early for mint. I’ll arrange them in the one of the vases and wonder if maybe I inherited more than the objects.

Well done Pammy, such fun seeing all those vases of your mum’s. I’m impressed with your arranging skills, definitely inherited, love A.

Hi Pamela,

What lovely thoughts you put together about your Mom she was very talented remember your gran, Auntie Pat telling us💕

Hopefully you arrived back in the UK safely and well and you all well.

It has been a sad time and I have been thinking of you all over the last couple of weeks.

Lots if love

Maryal💞💞💞💞

Pretoria, SouthAfrica

PS. Lovely picture of you.